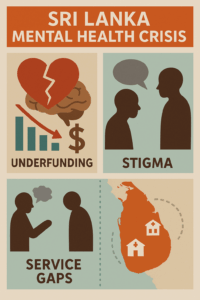

Three main issues affect mental health in Sri Lanka: limited finances, much stigma, and poor services, particularly in rural areas. Despite having effective policies, inequalities are still generated by inefficiencies and cultural factors. Approximately 13.3% of people experience untreated mental illness as a result (Mental Health in Sri Lanka A Summary – Join Health, n.d.; National Data – Directorate of Mental Health, n.d.). This review brings into question the perennial problems of underfunding, the absence of appropriately qualified professionals, and growing levels of drug abuse and suicide, especially in rural areas.

Persistent Underfunding and Gaps in Policy Implementation

A mere 1.6% of the total health spending in Sri Lanka goes towards mental illness, and the figure hasn’t changed since 2012 (Jenkins et al., 2012). The new Mental Health Policy for 2020–2030 has yet to face financing gaps, despite the previous one (2005–2015) focusing on decentralised, community care (Mental Health in Sri Lanka A Summary – Join Health, n.d.; Rajasuriya et al., 2021). For example, due to fiscal constraints, district-level community resource centres contemplated in 2017 remain a vision (Rajapakshe et al., 2023). The 2022 economic crisis put additional pressure on resources, with hospital overcrowding and late purchase of medicine undermining the quality of care (Knipe et al., 2017; Mental Health, All Is Not Okay | The Morning, n.d.). These underscore Sri Lanka’s long history of underinvestment in mental health, with only 5–10% of health spending going to mental health compared to other high-income countries (Jenkins et al., 2012).

Stigma and Cultural Barriers

The biggest challenge is stigma, with 75% of patients avoiding healthcare due to fear of discrimination (Fernando, 2024). The perpetrators of discrimination are most frequently employers themselves, who terminate employees who have mental illnesses more often than not (Fernando, 2024; National Data – Directorate of Mental Health, n.d.). Cultural attitudes of mental illness being “weakness” or “karma” discourage treatment, particularly among women whose marriages are then “tainted” if diagnosed (Fernando, 2024; Mental Health in Sri Lanka A Summary – Join Health, n.d.). Other than repeated anti-stigma campaigns, rural areas-where 62.7% of the population lives, have never been accessed with focused intervention, perpetuating myths (Mental Health, All Is Not Okay | The Morning, n.d.; Rajasuriya et al., 2021). According to a 2023 study, counselling or meditation was the stress coping mechanism of only 15.4% of rural adults, above hiding and concealment (Priyadarshani & Warnakulasuriya, 2023).

Workforce Shortages and Urban-Rural Disparities

Sri Lanka has 1 psychiatrist per 500,000, and clinical psychologists are fewer than five in the nation (Jenkins et al., 2012; Rajasuriya et al., 2021). Workforce shortages exist in tertiary hospitals in Colombo and Kandy with specialised services, while rural regions like Jaffna and Gampaha are particularly short-staffed. For example, 38% of the health centres have only mental health-trained nurses, and 34% lack medical officers (Jenkins et al., 2012; Rajapakshe et al., 2023). Community-based interventions, although laudable by WHO for deinstitutionalization (WHO Commends Sri Lanka Deinstitutionalization Approach on Mental Health | EconomyNext, n.d.), are reliant on hospital staff without autonomous funding, limiting outreach (Jenkins et al., 2012) . Psychotropic medication is not available in rural clinics, and patients must travel 50–100 km to have it renewed (Mendis, 2004; National Data – Directorate of Mental Health, n.d.).

Increased Rates of Substance Abuse and Suicide

Substance abuse and suicide rates are indicators of indifference at the system level. Heroin use grew 32% from 2015 to 2019, and 77% of users were dependent on regular doses (National Prevalence Survey on Drugs Use 2019, n.d.). Cannabis is the most prevalent illegal drug (1.9% of adults), with disproportionate use among poor rural men (National Prevalence Survey on Drugs Use 2019, n.d.; World Health Organization. Regional Office for South-East Asia, 2022). Suicide rates, while declining from all-time highs, increased again to 15.6 per 100,000 in 2020–2022, as a result of economic insecurity and availability of pesticides (Knipe et al., 2017; Mental Health, All Is Not Okay | The Morning, n.d.). 70% of the cases are rural in location, with hanging and organophosphate poisoning being the method of choice (Knipe et al., 2017; Mendis, 2004). Youth are especially prone, with 40.3% of them feeling anxious or lonely due to school pressure and conflict within the family (Rasalingam et al., 2022; Surenthirakumaran et al., 2021).

Conclusion

Sri Lanka is currently facing an acute mental health crisis owing to a dysfunctional governance system and an overburdened socio-cultural neglect. While community-based models hold out promise, inadequate long-term funding and the continuing stigma surrounding mental illness severely limit their scalability potential. Top priority in the immediate term must be accorded to increasing funding for mental health to 5% of the overall health budget, increasing training for rural primary care teams, and integrating anti-stigma curricula into schools. For sustainable development, there must be a coordinated effort by various sectors to address the causes of mental health problems and not symptoms alone, such as poverty and unemployment, both drivers of heightened substance abuse and hopelessness. Until there is a widespread and radical remaking of the system, the vision of equitable mental care for all remains frustratingly out of reach.